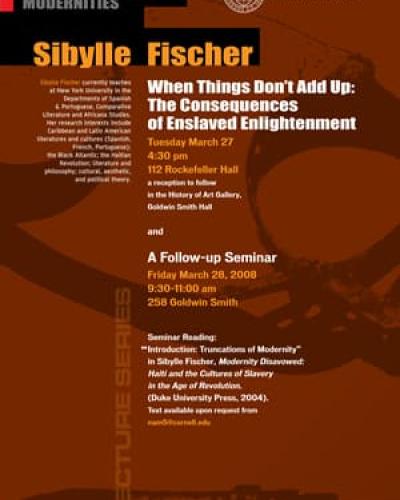

112 Rockefeller Hall

Sibylle Fischer is Associate Professor in the Department of Spanish and Portuguese, Comparative Literature, and Africana Studies at New York University. She is the author of Modernity Disavowed: Haiti and the Cultures of Slavery in the Age of Revolution (Duke University Press, 2004), a groundbreaking study which has received four major awards to date. As the first full account of the ramifications of the Haitian revolution in 1804 for the culture of the Hispanophone Caribbean islands during the nineteenth-century, the book is an important contribution to the study of Caribbean history and culture. It also develops a very innovative interdisciplinary methodology combining literary analysis with archival research in order to study the traces of an incompletely recorded history. Most apposite for the project of the Institute for Comparative Modernities, Modernity Disavowed also develops a new concept of modernity to account for the peculiarities of the experience of modernity in this particular non-European region. Fischer argues that the historical and cultural rupture represented by the Haitian revolution had to be actively disavowed in order to maintain existing hierarchies and that therefore the promulgation of European modernity in the islands is shadowed by the willful disavowal of the local revolution and its claims on modernity.

The lecture, consisting entirely of new work, essentially extended some of the main arguments about disavowal in Modernity Disavowed to the domain of political theory and offered an original resolution of a much discussed central contradiction in the work of the seminal philosopher of liberalism, John Locke (1632-1704), whose ideas were particularly central to the American Constitution. The contradiction concerns Atlantic slavery. Fischer outlined Locke’s economic and political connections to slavery during his time: He was an investor in the English slave trade through the Royal Africa Company and he also contributed to the drafting of the constitution of the Carolinas which codified the master’s absolute power over his slaves. This and other texts appear to be in direct contradiction with the main tenets of Locke’s philosophy, namely the absolute freedom and equality of men in a state of nature. Scholars have largely sidestepped the contradiction by suggesting either that the support of slavery was in some sense a worldly fault or error with no intrinsic bearing on Locke’s philosophy or that fundamental racism made him implicitly exclude Africans from the category of humanity, and hence from the human right to freedom and equality. Through a rigorous textual analysis of key passages in Locke’s writing, Fischer argued that, on the contrary, the question of slavery is central to Locke’s writing and that in the end it boils down not so much to a contradiction but to the complex disavowal involving the double negative encapsulated in the formulation: The African is not not human// the African is not not a beast. The ramifications of this argument for what is perhaps the fundamental tenet of philosophical (and political) modernity are potentially very great, for the argument suggests that the exclusion or demotion of non-Europeans and slaves from full humanity—and hence from freedom and from the autonomy of reason—is not introduced ex post facto, or fundamentally subsidiary to the major philosophies of the enlightenment, but rather intrinsic to them from the very start. The lecture was well-attended—with between 30-40 people in attendance—and drew a genuinely interdisciplinary crowd including students and faculty from History, Art History, Development Sociology, Government, Anthropology, Comparative Literature, English, Romance Studies and Africana.

We organized a follow-up seminar the following morning loosely organized around a reading of the introduction to Modernity Disavowed. Despite the unappealing time—9:30 Friday morning—and a freak snow storm, we had 10 people in attendance, two faculty members (Melas and Wong), six graduate students (Government, English, Romance Studies) and two undergraduates. We started with a general consideration of the text but the discussion really took off when students began articulating how the questions addressed there related to their own research. Had there not been a bus to catch the discussion could easily have continued another hour. As it was we had to break it off at 11:30.