Toboggan Lodge, Cornell University

Free and open to the public

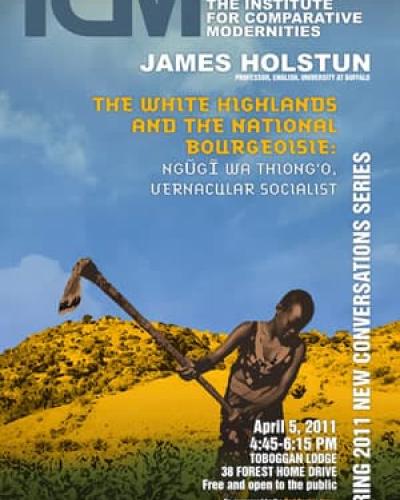

JAMES HOLSTUN (Professor, English, University at Buffalo)

Suggested reading:

Utopia Pre-Empted: Kett’s Rebellion, Commoning, and the Hysterical Sublime

Communism, George hill and the mir: was Marx a nineteenth-century

Winstanleyan?

I will argue that, in trying to understand Ngũgĩ’s work and his contribution to historical materialism, we should shift away from the predominant recent terms of culture and nation and toward land and the mode of production—though culture and nationalism come back in again, as secondary but important concerns. More particularly, two shifts in the mode of production in Kenya form not merely the backdrop for Ngũgĩ’s fiction, drama, essays, and autobiography, but their very substance, and an object of sustained theoretical meditation.

The first shift lies in the conquest of the Gĩkũyũ White Highlands, and the transformation of relatively autonomous Gĩkũyũ small producers into bound neo-feudal tenants or wage laborers, and Gĩkũyũ landholdings into the absolute property of white colonial planters. This transformation was an accelerated colonial version of that “primitive accumulation” Marx described in Section 8 ofCapital 1. Ngũgĩ did not focus his fiction directly on the formation of the White Highlands, but it is clearly visible in its aftershocks: the anomie and internalized wounds of agrarian dispossession, the remnants of commoning and other communal traditions in later Kenyan culture, the gradual and shocking discovery by his characters that dispossession was a historical event, not a metaphysical state.

The second shift is simultaneous with Ngũgĩ’s writing: the shift within the capitalist mode of production from imperial colonial rule from without to neocolonial rule from within and without by the national bourgeoisie allied with global finance capital. This prospect and process of defeat —and not the discursive aporias of “nation” and the defeat of grand narratives celebrated by postcolonial critics like Simon Gikandi—accounts for the melancholy infusing Ngũgĩ’s fiction from The River Between (written 1963) to Wizard of the Crow (2006). In this regard, his fiction is not simply influenced by but is also formally analogous to Josiah Mwangi Kariuki’s Mau Mau Detainee (1963), which warns against the “Land Consolidation Scheme” underway as Kenya gains independence; and Frantz Fanon’s Wretched of the Earth (1961), which prophesies the imminent popular struggle against the Algerian national bourgeoisie, and focuses on the land itself as the primary object of both colonial and neocolonial struggle.

In Ngũgĩ’s struggle against neocolonialism, melancholy doesn’t always prevail, partly because of his access to the resources of hope from Kenyan history, including the world of collective solidarity in peasant small production that preceded the creation of the White Highlands. We see this fascination with new/old collectives represented in the novels (for instance, the Ndemi-Nyakinyua Group of agrarian communalists in Petals of Blood), constituted by his novels (the combinations of novel form and oral narrative in his later works), and in his own cultural work: the communal theatrical praxis of the Kamĩrĩĩthũ People’s Theater, the International Center for Translation at UC Irvine. As self-conscious and totalizing “returns” to something that never fully existed, these efforts avoid the familiar postcolonial alternatives of naïve, reactionary, and impossible romanticism on the one hand, or on the other, a shattered, fragmented, and thoroughly academic modernity deprived of social utopia. By preserving these Gĩkũyũ and other African practices in a new communist project, Ngũgĩ becomes a “vernacular socialist” like the Christian communist Gerrard Winstanley in seventeenth-century England; the activist and theorist José Carlos Mariátegui La Chira in twentieth-century Peru, and the late Marx himself, who hoped that the traditional peasant commune or mir might be the fulcrum for revolutionary transformation in Russia.

Jim Holstun teaches world literature and marxist theory in the English Department at SUNY Buffalo (UB). He wrote A Rational Millennium: Puritan Utopias of Seventeenth-Century England and America (Oxford, 1987), and Ehud’s Dagger: Class Struggle in the English Revolution (Verso, 2000), which won the 2001 Isaac and Tamara Deutscher Prize for English-language marxist scholarship. Examining the popular praxis of Englishmen and women (tyrannicidal theorists and assassins, radical prophetesses and army privates, and agrarian communists), it argues that the failure of the English Revolution was the failure of land reform.

Holstun has written essays on lesbianism and English Renaissance literature; on Marx and the Russian peasant commune; on the British marxist historian, Brian Manning; and on chemical weed control and the deaths of his father and Mike Sprinker, editor of his second book. He recently completed a series of four essays on Kett’s Rebellion (1549), a rural anti-enclosure utopian project that was the greatest anti-capitalist revolt in British history. And for The Electronic Intifada, he has written or co-written four essays on Zionist propaganda in the US.

He has now left early modern England for the world of twentieth-century communism and the fight against neocolonialism. At UB, he has taught graduate and undergraduate courses in Palestinian literature, the African novel, the Arabic novel, Arab women writers, Ngũgĩ and neocolonialism, and feminism and marxism. He is now working on four essays: on Joseph Conrad’s “Outpost of Progress” (1896)—his brilliant anticipatory critique of Heart of Darkness(1899); on the conflict between magical and critical realism in the contemporary Arabic novel, focusing on Sahar Khalifeh’s The Inheritance (1996) and Elias Khoury’s Gate of the Sun (1998), both about Palestine; on Ngũgĩ’s drama and fiction and Kenyan primitive accumulation; and on the China writings of Agnes Smedley, the American proletarian, novelist, journalist, and communist.

CO-SPONSORED BY THE CARL BECKER HOUSE